Off the Wall and into the Pit: Sonic Revolt and the Vans Old Skool

Client: Vans

Long before the Vans Old Skool became a streetwear heavyweight, it was just a humble workhorse stitched together for skaters who needed shoes tough enough to survive the sun-bleached slumscape of Dogtown. No hype machine, no corporate blueprints, just a pair of waffle soles sticking to grip tape like your life depended on it. But somewhere between busted boards, punk rock and hip hop cyphers, the Old Skool became a scuffed up muse for the malcontent, leaving its mark on every curb, canvas and culture it collided with. With Vans launching the Old Skool Premium 'Music Collection' in celebration of the model’s raucous musical history, we’re looking back at how the Old Skool evolved from a Southern Californian skate staple to a global symbol of creative revolt.

Surf, Skate, Survive: Dogtown

During the mid-1970s, California was feeling the heat. The sunburnt state was wilting through one of its worst droughts of the century, leaving swimming pools empty and drainage ditches scorched. But while the extreme weather left water supplies spluttering, it also helped ignite a new phenomenon grazing knees and punishing soles across Southern California: skateboarding.

Born from the restless energy of wave-starved surf rats, skateboarding gained momentum as asphalt alchemists like the Zephyr Boys carved up empty pools, abandoned suburban yards and the concrete arteries of Dogtown, a crumbling seaside slum wedged between Santa Monica and Venice. By the tail end of the drought in 1977, Dogtown’s pavement beaters had a brand-new toy to crush –the Vans Style 36 that later became known as the Old Skool.

Served up to skaters with a waffle sole, the Old Skool’s diamond-shaped pattern clung to grip tape like thick Canadian maple syrup. Built with Vans’ signature vulcanised rubber sole, a process where rubber is heated with sulfur to create cross-links between polymer chains, the model provided skaters with lightweight grip, flexibility and durability. Unlike traditional cupsoles, which were heavier and required a longer break-in period, Vans’ approach delivered instant board feel straight out of the box. Up top, Vans utilised durable suede and canvas to forge a true curb-crushing workhorse, even going the extra mile by adding leather panels to protect against grip tape abrasion.

‘There was no leather around until ‘76 when we finally came up with the Old Skool,’ Steve Van Doren told us back in 2005. ‘Leather would never wear out. The outsole never wore out, the sidewall of the material would never wear out, and skaters could get it down to where there was just a little bit of fabric, but the sides would still be good.’ Finally, added padding around the collar provided crucial ankle insurance, while double stitching and reinforced toe caps made Style 36 battle-ready for Dogtown.

‘We were the perfect crash dummy test pilots,’ says Tony Alva, baron of the bowl and Z-Boys posterboy. ‘If you wanted to test the durability of a product, give it to the Z-Boys!’ Vans second ever skate shoe was also the first to feature the now-iconic Jazz stripe (originally known as Sidestripe), a rather divinatory doodle by Vans co-founder Paul Van Doren, as the Old Skool began dropping in on punk rock, hip hop and hardcore across Southern California.

The Misfits Circus

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, California’s punk scene had ignited. Bands like Black Flag and Dead Kennedys delivered gnarly warts-and-all soundtracks that mirrored the iconoclastic spirit of skateboarding and its restless pioneers. These bands weren’t just making music for skaters, they were skaters themselves. ‘My friend and I, Ian MacKaye, grew up wanting to be like the guys from Skateboarder Magazine,’ says Henry Rollins, frontman of Black Flag. ‘The classic photos of Alva, Peralta and Jay Adams, we always wondered what shoes they were wearing and found out they were Vans and we could mail order them to D.C.’

The Old Skool was built to withstand punishment in the pool and the pit – 'It was birthed out of pure technical functionality,' says Vans Archivist Catherine Acosta – but punk rock’s godfathers also embraced the Old Skool for another simple reason. Like skateboarders, they were fiercely territorial, and Vans had been marking its turf out in California since the 1960s. Punk bands even featured local skate legends on their album covers. ‘The era was so raw,’ says Acosta. ‘Venice Beach band Excel even used an image of Tony Alva rocking one of the first colourways of the Vans Old Skool for their EP Seeking Refuge.’

This connection between skateboarding and music was amplified in the decades that followed, and the Vans Warped Tour played a pivotal role. Kicking off in the mid-90s, it became the largest travelling music festival in the United States. A rolling celebration of skate culture and music, the tour featured half-pipes, live demos from legends like Tony Hawk and star-studded lineups that included Pennywise, Bad Religion, NOFX and Dropkick Murphys.

‘Overcrook Grinds and 808s

Throughout the 1990s, skateboarding had also carved its place within America’s fledgling hip hop scene. Future legends like Nas, Gang Starr, and Mobb Deep provided the soundtrack for some of the era’s most iconic skate videos. This cultural collision deepened over time, with hip hop embracing skateboarding’s defiant energy and the Old Skool emerging as an unexpected streetwear staple.

Longtime grip tape groupies Pharrell Williams,Nigo, and their Billionaire Boys Club imprint helped infuse hip hop with skate aesthetics in the new millennium, while Tyler, The Creator and his Los Angeles Odd Future crew formalised the crossover with a series of Vans collaborations. These included playful pastel Old Skool silhouettes adorned with Odd Future’s donut logo and the indelible Vans checkerboard motif – a throwback to the kids customising their Old Skools in class. And let’s not forget A$AP Mob and Pretty Flacko somehow seamlessly styling the Old Skool alongside their proclivity for precipitous price tags or Frank Ocean casually pulling up to the 2017 White House State Dinner in Vans checkerboard Slip-Ons.

Vans weren’t just laced, they formed part of hip hop’s lyrical lexicon. Earl Sweatshirt’s ‘Drop’ (‘Vans, we don’t rock Prada’), A$AP Rocky’s ‘Angels’ (‘Vans in my hand, had a plan to get richer’), and ‘Fish’ by Tyler, The Creator ('Vans on, feeling like a skater’) are just a few tracks that helped cement Vans and the Old Skool as enduring earworms in hip hop’s notoriously fickle fashion cycle.

The Vans Old Skool Premium Collection

Nearly five decades after its birth in California, the Vans Old Skool still retains the sole-mincing spirit of its raucous forebears. Music has always been at its core, and in 2025, Vans are cranking up the volume with the Premium Old Skool ‘Music Collection’.

The collection reimagines the Old Skool through the lens of three iconic musical eras. The Punk Capsule, inspired by the 1970s and 1980s, features bold leopard prints that channel the raw energy of punk and hardcore. The Warped Tour Capsule, paying tribute to the 1990s and 2000s, incorporates classic checkerboard and flame motifs reminiscent of the Vans Warped Tour era. Finally, the Hip Hop Capsule, representing the 2010s, showcases vibrant colourways with gum soles that reflects the underground hip-hop movement.

‘Since 1977, when the Old Skool first debuted, the style has organically grown as a footwear icon that captures Vans’ Off The Wall spirit while simultaneously becoming a wardrobe staple for many,’ says Diandre Fuentes, head designer at Vans. ‘That’s why we turned to music as a storytelling vehicle to speak about this evolution. The shoe has been organically adopted by so many iconoclasts and their fans throughout the years. And we hope that celebrating that history will inspire more folks to continue to push the envelope of style and culture alongside Vans.’

While the Old Skool Music Collection honours its deep-rooted sonic roots, it also receives a serious upgrade where it truly counts. Enter Sola Foam ADC, a next-gen insole tech that dials up cushioning for all-day comfort. The fit and build have also been fine-tuned for a smoother, more seamless ride, while sustainability takes centre stage, with biobased Sola Foam and regenerative volcanised rubber outsoles making this a greener take on the California classic. 'The naked eye won’t be able to catch all the tech we packed into the Premium Old Skool, but your feet will instantly feel the difference,’ says Fuentes.

After years of mangled decks, thrashed canvas, and cold-blooded sidewalk symphonies, the Vans Old Skool remains as resilient as ever. Kicked, dragged, duct-taped, it wears every scar like a battered badge of honour. Now it's back on its feet with the Old Skool Music Collection. The ‘Punk Capsule’ is available right now, whereas the 90s–2000s ‘Warped Tour Capsule’ lands on March 6 and the 2010s ‘Hip Hop Capsule’ follows on April 10.

ASICS Skateboarding Enters the Chat With the Leggerezza FB

Client: ASICS

For nearly three decades, Gino Iannucci has made the hard look easy and the simple look sublime. Now, the Long Island enigma with the mystical push brings that same low-key mastery to the ASICS Leggerezza FB – a silhouette as timeless as Gino's video parts.

It’s a no-brainer for ASICS Skateboarding. The Japanese sportswear giants have been carefully carving out their skate program over the past few years, taking a deliberate approach that leans on heritage silhouettes, performance tech from their running catalogue, and a roster stacked with genuine credibility – Akwasi Owusu, Shay Sandiford, Monica Torres, Emile Laurent, Kieran Woolley, Brent Atchley, Simon Bannerot, and the Ishizuka brothers among them. Rather than flooding the market, ASICS have been picking their moments: limited releases, thoughtful collaborations, and silhouettes like the Japan Pro and GEL-Vickka Pro that stay true to the brand’s distinct design language while delivering on-board feel and durability.

In an industry where skate divisions can sometimes feel like afterthoughts bolted onto bigger sportswear machines, ASICS have been playing a different game. The push began on their home turf of Japan, where they worked closely with local skaters, small shops, and respected photographers before gradually extending into the global market.

That timing wasn’t accidental. Skateboarding’s debut at the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games put the sport front-and-centre in ASICS’ own backyard, and the brand saw a rare opportunity to enter the category with both authenticity and a home-field advantage. Rather than rushing in with a massive global campaign, they opted to plant seeds locally, letting their credibility grow organically within Japan’s tight-knit skate community.

It’s a slow-burn strategy – not unlike how they built their reputation in the running world – and it’s winning them respect from skaters who’ve seen too many brands crash into the scene and burn out spectacularly.

The partnership between skate veteran Iannucci and ASICS began, fittingly, without fanfare. In 2020, Gino wasn’t even looking for a new sponsor. ‘I was skating $20 slip-ons from Target,’ he laughs – basic canvas, boat-shoe style. The kind you’d wear to take out the trash, not back tail a ledge.

That changed when longtime friend Kaspar, now working with ASICS, sent over a few pairs. ‘I wasn’t worried about them being a big brand, because they’d never been involved in skateboarding before – I thought that was kind of cool,’ Gino recalls. ‘The shoes he sent? I loved them, so I kept skating in them. It felt good to be on some other shit. I’d skated in Onitsuka Tiger years ago, when we were filming for [2003’s] Yeah Right!, so it wasn’t totally new to me.’

Around that time, Thrasher aired a clip with Chico Brenes for Chico Stix, and viewers quickly clocked the shoes on Gino’s feet. The buzz reached ASICS HQ, and before long, he was offered a spot on the team. ‘Once I knew who was involved, the shoes they were putting out, and the team they were building, I was all in,’ he says.

When Football Meets the Freezer

A few months later, ASICS flew their skate team to Japan for a closer look at what was coming down the pipeline. Among the prototypes and samples laid out, one silhouette jumped from the line-up – the Leggerezza FB. The design takes cues from the 1989 Injector Arezzo football boot, a low-cut model built for quick cuts and close control.

For the shoe’s designer, Yasuyuki Takada, the reaction to working with Gino was immediate. ‘I remember thinking it was unbelievable to be making a product with him,’ he recalls. ‘It was a huge honour for both ASICS as a brand and for me personally, as a product designer. The more I learned about his career and legacy, the more I understood how incredible this opportunity really was.’

On why the Injector Arezzo was the perfect jumping-off point, Takada explains: ‘It had this rare combination: simple yet bold design. Its slim build offered agility which felt like the perfect insight for skateboarding performance.’

Indoor football silhouettes have a deep history in skateboarding. Long before purpose-built skate shoes became the norm, riders gravitated toward low-profile indoor styles for their slim fit and precise board feel. The Leggerezza carries that tradition forward, adding ASICS’ own technical edge: a durable cupsole tuned for flick, an upper that blends premium leather with reinforced zones, and a snug fit that wraps the foot without dead space.

‘Our highest priority was delivering comfort within a slim silhouette,’ says Takada. ‘The biggest challenge was ensuring adequate cushioning and support while working with a thinner tooling.’

Starting with the silhouette, Gino layered in details from another sport that shaped his youth: ice hockey. The blades were as familiar as the board, so he built in a subtle hat-tip to that icy past. The laces, for example, are waxed – a detail borrowed straight from mid-80s hockey skates. ‘It just makes things harder to loosen up on you,’ he explains. ‘The wax really keeps it all together. I thought it would be a nice thing to add to a skate shoe, in case you don’t want to tighten them too much. I hate anything slippery – metal eyelets, slick laces. This keeps it locked in.’

The Leggerezza’s cosy fit, low profile, and featherweight build live up to its name – ‘leggerezza’ means ‘lightness’ in Italian – and match Gino’s effortless, almost weightless skating style. ‘The toe box sits right above your toes – no extra space to wriggle around,’ he explains. ‘Same with the heel – you don’t have to crank the laces to get a good fit. It’s light, it’s thin, and it gives me as much control as possible, which is exactly how I like it.’

The debut drop comes in two colourways: ‘White/Pure Gold’ and ‘Midnight/White.’ The former channels the clean, almost regal look of classic indoor boots, while the latter opts for a deep navy leather that oozes timelessness. ‘White indoor shoes have always looked clean to me,’ the athlete says. ‘And navy leather… it’s just classic.’

That same understated precision carried into the launch itself – no velvet ropes, no influencer stampede, just a tight 100 heads in the know. ASICS and Gino set up shop at Café Belle on Mulberry Street, a cozy Lower Manhattan hideout with family ties that run deep. The café belongs to Gino’s wife, Noelle Scala, and was passed down from her father, which made the setting more than just a backdrop – it was a family affair, echoing the way ASICS have always kept things close-knit. The guest list was pure skate brains trust, plus friends and fam. Intimate, personal, and utterly on-brand – the kind of night you actually want to be at, not just post about.

For Takada, the journey was as much about this kind of personal connection as design. ‘The most rewarding part is the constructive dialogue – not just about shoe design, but about building the brand within the skateboarding world,’ he says. ‘The connection between the brand, the skateboarding community, and the consumer feels much closer than in other categories. We faced challenges – different locations, languages, cultures, and backgrounds – but everyone involved put in a lot of effort and passion to bring it together.’

Patience Is Power

What sets this collaboration apart isn’t solely the shoe – it’s the way ASICS are moving. While other brands have built their skate divisions into huge, global marketing juggernauts, ASICS are taking a more intimate path. Their first skate drops were Japan-only, and while their rider roster spans continents, it stays tight. Their releases feel more like capsule collections than mass-market product waves.

Part of the excitement around this collaboration is simply that it’s Gino. In an era where content is constant and personal brands are built on oversharing, he has remained a man of mystery. His footage is sparse but surgical. His style is studied without feeling forced. And his Poets brand operates in much the same way – small drops, thoughtful design, zero noise for the sake of it.

‘My kids, my lady – that’s my inspiration,’ he says. ‘ASICS are also a big reason why I’m skating as much as I am these days. I feel like I mean something to them… and because of that, I want to come through for them.’

The Leggerezza FB isn’t another canned sneaker – it’s proof that ASICS are serious about playing the long game in skate. They’ve brought in a rider whose career is defined by taste and restraint, revived a heritage silhouette with deep crossover appeal, and done it all without pandering to the hype cycle. Instead, they’re letting the product – and the people wearing it – speak.

If history’s any indication, the Leggerezza will slot into Gino’s rotation for years, not seasons. And for ASICS, it could be one of those shoes that helps anchor their identity in skate for years to come. Minimal, considered, and built to last – just like the man himself.

From Long Island to your local – the ASICS Leggerezza FB is in stores now.

Blood, Sweat and Spin Kicks: The Sneakers of Aussie Hardcore

Client: Foot Locker

Live music venues across the sunburnt country continue to thunder with homegrown hardcore talent. Hammered into shape by antecedents like Massappeal, Toe to Toe and Mindsnare, the new kids on the block still carry the fierce DIY attitudes and political vehemence of their predecessors, while also finding space to discover their own lung-punching pitch and style. Inextricably tied to the Air Max culture rampaging across the country, the next generation of hardcore has never been louder. So keep your liquids up and lather sunscreen liberally, these are some of the sweltering sneakers that define Aussie hardcore.

From the US to Terra Australis, Air Jordan Joins the Fray

Throughout the late 1970s, the sound of hardcore’s guttural lyrics poured out like concrete in cities across the United States. Underground movements were thriving, anointing new cult heroes like Black Flag in Cali and Bad Brains in Washington. But hardcore wasn’t only kicking up the tempo in live venues. Taking cues from hip hop, a genre also in its embryonic stages in the 1970s, hardcore ditched the Dr. Martens for sneakers and distanced itself from the sartorial peacocking of punk that was typified by its visionary linchpin, Vivienne Westwood. It was function, not form, that reigned supreme, and sportswear took centre stage.

It was for this reason that hardcore fell in love with sneakers like the Air Jordan 1. Whether bands were aware of the North Carolina prodigy getting air in Chicago or not, the performance-oriented Air Jordan 1 was lauded for its stoic durability in the pit and beyond (the silhouette was getting thrashed even in the skateparks of Southern California). Ray Cappo, the vocalist for the band Youth of Today says, 'Here’s what’s funny. I got the Air Jordan 1 KO at Marshall’s cheap! Because I thought they looked cool, they were cheap, and they were canvas as I was veg.'

By the mid-80s, hardcore was booming and local scenes were sprouting across the globe. Even in the far flung reaches of Australia, artists were lacing the Air Jordan 1. One such artist was Massappeal, who are forever remembered in hardcore folklore Down Under as one of the preeminent acts from the Harbour City. Band co-founder Brett Curotta recalls, ‘I had a pair of Air Jordan 1s in 1986, but they actually had a red Swoosh, which I hated! So I got a shitty black marker and blacked-out the Swoosh'. Even though hardcore music transformed throughout the following decades, some philosophical underpinnings remained, like the fierce DIY attitude – marker pens and all.

Hardcore culture from the US had originally filtered through to Australia via zines and tapes back in the 1980s, but by the late 90s and early 2000s, the Great Southern Land was hosting its very own hardcore festivals. Resist Records, an independent store and record label based in Newtown, Sydney, hosted one of the first: Hardcore 2000. Located at the Iron Duke Hotel in Zetland, the 200-capacity venue was a space to promote and amplify homegrown talent.

‘I wanted to showcase some of the country’s best hardcore bands,’ says founder Graham Nixon. ‘Hardcore Superbowl was another annual punk festival running a few years before Hardcore 2000. My idea was to replicate what they were doing, but have a lineup of mainly hardcore bands who were unlikely to play at the Superbowl.’

At both Hardcore 2000 and Hardcore Superbowl, mainstays like the Air Max 90, Air Max 95 and Air Max 97 regularly stomped through sets in Sydney, but it was the rowdy introduction of a seven-bubbled beast that truly cemented itself as a hardcore headliner in the new millennium.

Batten the Hatches: Tuned Air and Beyond

In the 2000s, hardcore began to collide with a sneaker juggernaut running roughshod over Sydney and Melbourne: Foot Locker's Nike TN. Arriving with brawn and bravado in 1998, the sneaker was created by rookie designer Sean McDowell, who got inspiration for the model from the palm trees and sunsets in Florida. But for a lot of sneakerheads Down Under, the TPU feature resembled agitated, varicose veins and the sunset-like gradient sparked images of Sydney’s spray-painted entrails. The silhouette quickly became the baddest shoe on the block – ‘I always wanted the TN because of their tough **** status,’ says hardcore photographer Chris Roese.

It’s no surprise that the TN’s belligerent reputation still courses through its TPU veins, and its red-line mythology remains popular throughout the current breed of hardcore bands, including Sydney behemoths SPEED. Comprising of Dennis Vichidvongsa, Josh Clayton, Kane Vardo, and brothers Aaron and Jem Siow, SPEED surged in popularity during Sydney’s interminable lockdowns, and they’re now relishing the chance to play in front of their fans – blood, sweat and Air Max all inclusive.

Clayton says, 'Australia is very influenced by street fashion – TNs, Air Max 95s, Air Max 97s. I remember seeing the 'Infrared' colourway and thinking, "Fuck, I need those"'. He continues, ‘Hardcore has always been synonymous with sportswear. It’s just very easy to wear, which makes sense for the live performances.'

This unconditional love of Air Max is shared by fellow hardcore Sydney-sider, Trent, from the band Relentless. ‘I personally have always been so drawn to Air Max sneakers, especially the Air Max 1s. Fashionably, they are my favourite Air Max silhouette. They pair perfectly with some baggy jeans or Dickies and support me enough to move around on the stage and in the pit!’.

Back in the Pit with Air Max

These live performances have become a focal point for hardcore acts, especially after diehard fans were left stranded behind computer screens during the pandemic. It’s something that punk acolytes share with sneakerheads all over the world: the resolute sense of community.

‘When you’re bonding over something so niche, you can really relate to each other a lot better,’ says Aaron from SPEED. ‘A lot of people I know through hardcore are people I never would have encountered in my life were it not for the fact we had this common interest. I think if you see someone wearing a pair of really rare sneakers, it’s a similar experience.’

With the next generation of Air Max and Aussie hardcore well and truly upon us, it’s hard to imagine the air getting sucked from hardcore's lungs, or shoes, anytime soon.

Get your feet into the fray at Foot Locker – the home of all things Air Max.

Feet-First Into the Machine: The Rise of AI-Generated Sneakers

Sneaker Freaker, issue 49

Artificial intelligence is travelling at warp speed, beaming out endless spools of neo-Edo Nike temples, matrimonial Air Max and sneakers that look like they’ve crash-landed on the set of a Ridley Scott sci-fi flick. We’ve seen a revival of the Italian Renaissance, techno-coloured TNs sparked by electric fever dreams, and Swoosh stores teetering on the edge of post-apocalyptic worlds. Buckle up as we take the red pill route and travel deep inside the algorithm to comprehend AI’s circuit-breaking impact on the future of sneaker design.

Shock Me Like an Electric Heel

There’s already enough AI-powered sneaker design floating about social feeds to fry hard drives and melt synapses. Some are blatantly cartoonish, while others throw baroque, scientific and even convincing vintage patina into the mix. Take, for instance, the AI artist known only as Str4ngeThing, who went viral with Renaissance-inspired streetwear that looked a lot like Jerry Lorenzo had secured a Medici family commission in the 16th century.

‘AI is going to play a huge role in the future of sneakers. We all take ideas from each other. But now, by giving AI loose creative freedom, we can take inspiration from ideas that were once unimaginable,’ says Str4ngeThing.

The sentiment that AI will help break open new creative frontiers of the human mind was echoed by many of the artists we spoke to. ‘The limits of imagination are expanding beyond what has ever been possible before,’ says Sean Sullivan, a Portland-based creative director. ‘It’s our job to push forward and constantly explore and redefine those limits.’

Patterns and Paradigms

At its most basic level, generative AI creates images and words based on a variety of inputs, such as text, sounds, animation and more. The module will detect patterns and paradigms within existing data to generate reconstituted content in the form of (literally) anything – from Eminem vocals to accurate sports roundups for newspapers and intricate sneaker designs. The list of potential outputs is as endless as the inputs are creative. If you’re keen to get cooking, check out the AI-tech available from Midjourney, DALL-E, Stable Diffusion and Artbreeder.

‘The results can be quite random, but they also depend on the input and the AI model’s training,’ says Benjamin Benichou. ‘By providing the AI with specific guidelines and examples, we can somewhat control the output while still leaving room for creative and unexpected results.’

Generative AI is constantly evolving because researchers are combining the best attributes of different models with super-computers that actively seek out billions of extra data points. The ultimate Promethean tool for engineers, scientists, researchers and – you guessed it– sneaker designers, is therefore still in toddler mode, although it’s learning fast.

The Death of Artistry

Given generative AI already produces undeniably impressive visuals, the techno-Faustian pact to power up workflows and produce a kaleidoscope of imaginative content in mere minutes has obvious commercial appeal. But there are ethical quandaries associated with its use, among other more lethal possibilities such as ultra-realistic deep fake videos.

The art world has already provided several pivotal moments that have illuminated the difficulties of policing ownership and creation in an AI-enhanced world. In September 2022, the Colorado State Fair became the unassuming battleground for this debate. Jason Allen, a videogame designer from Pueblo, submitted artwork for a competition using Midjourney and Gigapixel AI software – tools that convert lines of text into hyper-realistic imagery. Allen spent roughly 80 hours on his piece, Théâtre d’Opéra Spatial, and after the judges awarded him first prize and a $300 cheque, it didn’t take long for the internet to sound off.

‘We’re watching the death of artistry unfold right before our eyes – if creative jobs aren’t safe from machines, then even high-skilled jobs are in danger of becoming obsolete. What will we have then?’ one commentator Tweeted. ‘Vacation time,’ quipped another user in response.

For his part, Jason Allen exonerated himself based on the fine print in the competition guidelines. ‘I won and didn’t break any rules,’ he told The New York Times.

Months later, Boris Eldagsen won the Sony World Photography Awards with Pseudomnesia: The Electrician. He later declined the W, citing philosophical issues. ‘AI images and photography should not compete with each other in an award like this,’ he wrote in a statement. ‘They are different entities. AI is not photography. Therefore I will not accept the award.’

Field Skjellerup, who posts content as @ai_clothingdaily, is well aware of the contradictions and potential for hypocrisy. ‘The underlying discussion surrounding influence and originality is present in art and design regardless. How is using a trained dataset of photos to synthesise new imagery from multiple influences any different from screenshotting people's work on Pinterest and putting them on my mood board for reference as a designer? Is it only that the whole process is now automated and can be operated in one swift motion that we have a problem?'

Feeding the Machine

The AI regulation debate raged and evolved throughout 2023, as lawmakers, lawyers, artists and authors tussled over myriad complexities. In May, Sam Altman, CEO of ChatGPT parent company OpenAI, revealed his biggest fears before US Congress. ‘I think if this technology goes wrong, it can go quite wrong.’ In a question-and-answer session that lasted nearly three hours, Altman called on Congress to create safety standards and carry out independent audits. The same month, Geoffrey Hinton, the so-called ‘godfather of AI’, left Google, warning of the impending threat of a technology he helped conceive.

The paperwork is piling up fast. In August 2023, a Washington federal judge ruled that AI-generated artwork is not eligible for copyright protection as it is created without ‘human involvement’. That decision backed the U.S. Copyright Office, as it asserted the same principle in March, though the case is still under appeal. Adding a few words of text to an image generator therefore does not constitute an act of authorship and can’t be copyrighted. Where that leaves IRL sneakers designed by AI is another nebulous matter that will undoubtedly be tested in court in years to come.

In September, a group of authors (including Pulitzer Prize–winner Michael Chabon) sued OpenAI in San Francisco, accusing the company of feeding their work to ChatGPT for training purposes. It’s the third copyright-infringement class action filed by authors against OpenAI. For context on why creatives are so incensed, try asking ChatGPT to tell you a joke in the style of Sarah Silverman – another writer pursuing redress through litigation.

System Overload: Blended and Barfed Out

Steven Smith, a design veteran at New Balance, Reebok and Nike, and now head of industrial design at Donda, views generative AI as a form of technological regurgitation. I ask him whether sneaker designers will even need to sketch anything in the future. Will they simply log into work and punch a few keywords into AI algorithms?

‘If you want a blended output of pre-existing content barfed out at you, go for it. I would rather use the power of our own minds to pave a new direction,’ he says. While Smith does find some generative AI sneakers interesting, he also feels it’s ultimately just a ‘distorted conglomerate of what’s already in existence’.

Having worked in the industry for over three decades, Smith’s analogue bullshit detector is just one of his finely tuned skills. He’s never been afraid to ruffle feathers or burn a bridge or two, but for Smith, AI will never replace the fundamental processes of blood-and-guts inspiration. ‘Generative AI is just another tool to me,’ he says. ‘It may lead you downa different aesthetic, but it’s no substitute for humanistic design. We try to deal with real thoughts and ideas.’

Skynet in Other Words

For many of us, the thought of rampant AI sparks a particular set of dystopian images – robot arms scything through elevator doors, biker jackets and metallic splooge – Skynet in other words. Regardless of how good Arnold Schwarzenegger looks in 2029 Los Angeles, AI is forcing many industries – fashion, scriptwriting and journalism to name just three – to stare down further existential threats.

‘Top people in the field are super worried,’ says Colm Dillane, founder of KidSuper. ‘It’s bad and getting out of control. I mean, AI is probably going to read this and go after me first.’

Known for his distinctively hand-crafted apparel, Dillane recently collaborated with Louis Vuitton for the Fall/Winter 2023 menswear collection. He is, among all of those invested in the fashion industry, a poster boy for relentless DIY attitude.

‘Is AI a threat to jobs?’ I texted him.

‘A thread to humanity,’ Dillane replied, ironically, auto-corrected.

I pose a similar question to ChatGPT. ‘Will AI make human sneaker designers obsolete?’ The response reeks of boring management-speak, a criticism many have made of AI-generated text. ‘The future lies in harnessing the collaborative potential of AI and human designers, resulting in a synergy that pushes the boundaries of innovation and elevates the field of design to new heights.’

That utopian sentiment is reiterated by Benjamin Benichou. ‘The potential for AI to revolutionise the creative process is immense. AI will enable creatives to push the boundaries, automate repetitive tasks and explore new aesthetics and forms. In the future, we can expect to see a more collaborative relationship between humans and AI, where each party brings their unique strengths to the table.’

Steven Smith, for one, is not fazed by the creative paradox – it’s the ‘Mr Anderson’ characters deep in the matrix who want to save a few dollars that ring his bell. ‘What alarms me is the businesspeople thinking it’s a substitute for the endless possibilities of a human mind. The mentality of AI being used by non-visual thinkers to replace us is alarming.’

Collaboration is an addictive buzzword that has provided unadulterated rocket fuel for the sneaker industry for close to 20 years, though nobody envisaged it would also describe the relationship between human designers and machines. While sci-fi films and piles of industry open letters will point to the ominous blinking red lights at the end of the doomsday tunnel, a symbiotic relationship between humankind and machine seems the most likely outcome. At the very least, we’ll have some wild sneaker heat for our feet when the Day of Reckoning™ arrives.

From Dancehall to Hip Hop: A Sonic History of the Clarks Wallabee

Client: Clarks Originals

Few shoes can rival the soaring global passport of the Clarks Originals Wallabee. Born in Killarney, Ireland, the Wallabee has been laced by Jamaican dancehall DJs, waxed lyrical by New York’s hip hop godfathers, and stomped inside the sticky, acid-house clubs of Manchester.

Brace yourself: this is the thumping sonic history of the Clarks Wallabee – a model inextricably tied to the story of beat-making.

The Clarks Wallabee was born in 1967. Originally inspired by a German moccasin known as ‘The Grasshopper’, Clarks acquired a licence to manufacture their own version, which became the legendary silhouette known today.

Manufactured with ultra-tasty-looking, cheese-like soles and idiosyncratic suede uppers, the Wallabee became a footwear wunderkind shortly after its inception. Beautifully bound with moccasin-stitched, rolled-edge vamps, the silhouette is still undoubtedly one of the most recognisable designs in the footwear industry.

Offering supreme comfort thanks to the naturally squishy, full-length crepe soles, the model does a sterling job of distributing weight across its entire surface. Above the sole, the Wallabee is manufactured in both low or boot-cut heights, making it roomy and forgiving enough for any type of foot.

Thankfully, it also hasn’t changed much since the 60s.

Despite occasional material overhauls, the silhouette has lost none of its inimitable shape or attitude over its half-a-century lifespan. Reborn in various guises, the Wallabee initially found a second home some 4500 miles across the North Atlantic Ocean in a city booming with Jamaican dancehall.

Nobody loves Clarks like Jamaica. Adopted by the rudeboys and rhapsodised by dancehall artists, classic models like the Wallabee became footwear with unassailable prestige in the island nation. Even a ban on foreign-made shoes throughout much of the 1970s couldn’t stop Clarks fever, with touring Jamaican musicians smuggling back piles of the revered shoes in their suitcases. Some even travelled to stores in the small village of Street in Somerset, where you could find ‘seconds’ (shoes with slight imperfections). For Clarks disciples, this was Mecca.

Back in the UK, British artists were also finding stylistic provocation in the Wallabee. In 1976, David Bowie and Iggy Pop hooked up for a tour to support the album Station to Station, with Bowie regularly lacing the model on and off the stage. Bowie also appeared on the classic television show Soul Train, ‘the hippest trip in America’, delivering a landmark performance in the beloved Wallabee.

Whether in Kingston clubs or stadium tours across Europe and North America, artists were beginning to find sartorial relevance in the unique characteristics of the Wallabee, and the volume was only going to get louder throughout the next decade.

The globe-trotting Clarks Wallabee began to appear in New York City’s booming, beat-making boroughs during the 1980s, thanks largely to the steady flow of Jamaican migrants bringing their rudeboy style.

Laced by up-and-coming rappers like Ghostface Killah, Raekwon and Slick Rick, the Wallabee helped establish hip hop’s style during its all-important formative years, and the model became an essential ingredient for the East Coast aesthetic.

With sneaker culture erupting in the 1980s, the Wallabee refused to get kicked to the curb, repeatedly rearing its head as a classy alternative. Immortalised by spitfire bars and the surging popularity of hip hop, the Wallabee was soon broadcast to the world.

It wasn’t just hip hop’s rising stars falling for crepe soles, either. Across the pond, Manchester’s legendary acid house scene (affectionately dubbed the ‘Second Summer of Love’) saw clusters of Wallabees stomp in abandoned warehouses, fields and immortal clubs like The Haçienda. Because you couldn’t wear trainers at the venues, the Wallabee became the obvious footwear of choice for bleary-eyed, nocturnal ravers, with the silhouette once again offering an appealing gateway between sneakers and more formal footwear.

Part of a subculture simmering from within Margaret Thatcher’s England, the Wallabee – like acid house – served as a canvas to express non-conformist attitudes. A notion that’s remained inextricably tied to the Clarks Wallabee.

The 1990s was another seismic decade for the Wallabee. In 1996, Ghostface Killah – the self-anointed ‘Wallabee Champ’ – released his classic debut album, Ironman. The LP cover art was replete with gaudy, colourful Wallabees that Ghostface dyed in preparation for the shoot. The album cover art now belongs to the aesthetic annals of East Coast rap, and it helped compose a hip-hop vernacular where the Wallabees stood front and centre.

Dedicating entire songs and even compilation LPs to his much-flaunted moniker, Ghostface became the poster boy for an entire hip hop movement consumed with Wallabee-mania. The Wu-Tang Clan, of course, stunted the Wallabee, while rap royalty Slick Rick, Run DMC, Notorious BIG and MF Doom would all jump on the rollicking bandwagon throughout the 1990s and early 2000s.

Clarks would even pay homage to the model’s deep New York City roots, with MF Doom receiving his own pair of custom New York Knicks-inspired Wallabees in the mid-90s.

In the UK, the Brits were again finding their own way of lauding their Somerset silhouette. With Britpop taking over the airwaves via the likes of Blur and Oasis, it was the lesser-known The Verve who really shined a light on the Clarks model.

Inspired by their love of psychedelic rock and Clarks, The Verve built on the legacy of their sartorial godfathers – the mods. The Wallabee graced the cover of their chart-topping Urban Hymns before appearing in the iconic music video for ‘Bitter Sweet Symphony’.

Clarks’ partnership with Futura in the 2000s kickstarted a blinding golden period for the Somerset label and their collaborative endeavours. Tapping a stalwart of the New York City graffiti scene, Futura produced a duo of Wallabees in the 2000s, and his colourful, paint-splattered sophomore iteration was no doubt the favourite among Wallabee aficionados.

The 2000s also saw the Wallabee ride shotgun with Walter White during his notorious rise to power in AMC’s Breaking Bad, becoming his footwear of choice despite the transformation from Mickey Mouse to Scarface. Later, BAIT paid homage to the legendary series by linking up with AMC for two unique Wallabee iterations – one referencing Heisenberg’s empire and the other inspired by the series’ bloody climax.

Let’s also not forget the rollicking, lumberjack-ready atmos collaboration that landed right before the close of the decade in 2009!

Collaborations were de rigueur for the footwear industry during the 2010s, and the Clarks Wallabee was enthusiastically stamping its global passport. Headlined by their duo of epic MF Doom collaborations in 2014, Clarks once again paid homage to East Coast hip hop with their Supreme link-up one year later.

Clarks continued to turn up the volume on the Wallabee’s flawless hip hop credentials throughout the decade – a watershed moment no doubt involving an official partnership with Wu-Tang’s Wu Wear to commemorate the 25th anniversary of 36 Chambers.

Still, it wasn’t just East Coast rappers lining up to remaster the Wallabee. Canadian rapper Drake and his OVO imprint sent Wallabee production to Italy with four handmade renditions, and the 6 God showed the kind of sophistication we’d love to see courtside!

Clarks didn’t take their foot off the accelerator upon entering the 2020s.

In fact, A Bathing Ape’s collaboration with Clarks in 2020 highlighted the shoe’s already stunning impact across the globe. Reflecting the growing popularity of the Wallabee in the fashion-centric districts of Harajuku and Shibuya, the model started the 2020s with a chest-thumping bang from the Ape. Showcased with a lookbook featuring England and Chelsea footballer Raheem Sterling (Clarks’ very first brand ambassador), the collaboration featured BAPE’s signature camouflage print – although this partnership did everything but blend in.

Later the same year, even rap royalty and Queens native Nas made an appearance for Aimé Leon Dore. And the quintessential NYC label knocked it out of the ballpark with four Wallabees manufactured using textured Casentino wool.

This year, we’ve also seen arguably some of the best renditions ever for the Wallabee. Between Bodega’s Autumn/Winter 2022 capsule, Jun Takahashi’s Undercover colab and in-house renditions like the Sashiko pack, the great footwear chameleon is still in phenomenal shape.

As well as stamping its real-world credentials, the Wallabee has also permeated the world of NFTs, linking up with Compound for a ‘Floor Seats’ collaboration (which features both a real shoe and an NFT component).

Inspired by a courtside NYC basketball experience and the Wallabee, Compound tapped BK the Artist (who recently developed Jadakiss’ last solo album artwork) to design a limited-run, animated NFT channelling 90s hip hop.

Launching at Art Basel in Miami this year, the collaboration is a vision of the future for the Clarks Wallabee – a model that’s never been afraid to challenge the status quo.

Does the Wallabee’s thumping sonic history strike a chord?

Air Max and Alienation: The Sneakers of UK Grime

Sneaker Freaker

Blasting from pirate radio stations at 140bpm, grime’s rapid-fire breakbeats reverberated from council estates in the early 2000s. Mutating from garage, dancehall and jungle, grime’s crude, cathartic sound delivered an honest portrayal of East London’s struggles in a new millennium. One of the most anarchic ascents in British music history, this is the story of how style and sneakers helped grime’s frenetic poets plough forward in search of a new identity.

‘Grime was about alienation’, says Simon Wheatley, author of Don’t Call Me Urban! ‘It was raw and painful.’ By the early 2000s, London’s council estates were flooded with young MCs desperate to articulate the struggles of their hand-to-mouth existence. Transmitted by pirate radio stations like Rinse FM, Deja Vu FM, and Heat FM, grime slowly found a voice through the static.

At the same time, American hip hop had become an economic and cultural powerhouse. MTV beamed out from televisions across London, and 50 Cent’s debut album Get Rich or Die Tryin’ was advertised on billboards, bus stations, and trains across London. In some ways, the LP had become allegorical for grime.

‘Grime reflected the desperation of living in deprived circumstances’, says Simon. ‘But it also celebrated absurd material values. It wasn’t just about being able to buy a house and look after your family. There was an aspiration to be a billionaire.’

The sense of social and economic alienation splintered London’s poorest boroughs. For this reason, underground events like Lord of the Mics (LOTM) provided an important remedy for artists looking to share their lyrical talent.

Often filmed in grubby basements, LOTM was founded by Jammer and Chad ‘Ratty’ Stennett in 2004. Battling over grime’s syncopated breakbeats, MCs like Skepta, Kano and Wiley all eventually participated in the clashing. For a long time, grime lacked a fundamental aesthetic because it only existed on pirate radio. LOTM provided grime with a space to physically manifest.

‘Being able to wear something that was fresh – that was everything.’ explains Natalie Onofua, founder of the website Higher Melody. ‘The Air Max 95 was huge, because they were affordable. If you came out wearing a pair of dead, beaten-up shoes, you’d get cussed.’

Originally designed by Sergio Lozano, the anatomical Air Max 95 was nicknamed ‘110’ for their price, and set a paradigm for Air Max obsession within grime. With the genre still mostly confined to clandestine radio airwaves and underground battles, grime struggled to reach a global audience, so wearing a simple Nike tracksuit and Air Max sneakers quickly became the loudest flex.

For grime’s earliest adopters, it was all about finding creative ways to stunt your fit without burning a hole in your wallet.

‘A big thing for us was colour coordination’, Natalie remembers. ‘We’d swap out our 110’s laces to match our tops and hair ribbons. We didn’t have much money, so getting acknowledgement from your peers was everything.’

But for a long time, bigger brands like Nike weren’t eager to sponsor grime because of its associated violence. One of the first groups to break through was More Fire Crew from Waltham Forest, East London. But in the video clip shown on MTV, the Nike sweaters and sneakers were all blurred out – an irony considering the huge capital brands would amass from the movement in the following decades. (Dizzee Rascal, for instance, one of grime’s godfathers, released his first sneaker collaboration in 2005: the Air Max 180. He followed up with the Air Max 90 ‘Tongue N Cheek’ in the leadup to his 2009 LP.)

Jordan Hughes, a photographer for NME magazine, was witness to the second wave in 2015, when grime’s raucous sound had ears ringing across the globe. For Jordan, grime was less besotted by US hip hop’s materialist peacocking, and more concerned with establishing its own British identity. ‘For US hip hop, it’s all about looking like you’ve got as much money as possible’, he says. It’s a notion further explored in the lyrics of Skepta’s ‘Shutdown’: ‘You tryna show me your Fendi / I told you before, this shit don’t impress me’.

The idea of a British identity was also apparent in Skepta’s first sneaker collaboration: the Air Max 97 SK. ‘That was a huge moment for everyone in 2017’, says Jordan. ‘Like Dizzee, here’s another relatively normal guy with a Nike collaboration. For us to get recognised globally, it was huge.’

Modelled on the unique geographical palette of Morocco, the Air Max 97 also took aesthetic cues from the Air Tuned Max – a sneaker beloved by Skepta in his youth.

But as artists like Stormzy, Skepta and Dizzee Rascal continue to launch high-profile collaborations with the likes of Nike and adidas, there’s still a deep sense of nostalgia for those documenting grime’s fledgling years in East London. For Simon, what began as a guerilla ascent powered by pirate radio and DIY software in some ways became a disappointing ‘reflection of corporate America’. And as grime became more commercially successful, the wardrobes reflected the newfound wealth.

‘Now it’s all about flossing because there’s money around’, argues Simon. ‘It’s all about the Gucci and Prada trainers. Even for the fans of grime. We’ve got this ridiculous situation now where people living in a council flat are spending 250 pounds on a pair of trainers. It’s just absurd, really.’

Has grime managed to establish its own unique identity, or has it conformed to American cues from across the pond? Furthermore, can ‘corporate American’ help emblazon a path for young British artists, or is it a marriage based on the bottomline? As grime continues to evolve and manifest in new frequencies like drill across the globe, Jordan believes the paradigm is shifting. In his mind, the community is now more aware than ever of the impacts of fashion.

‘I think a few years ago, we became very aware that high fashion labels generally weren’t using black culture in a positive way.’ Jordan argues. ‘It wasn’t helping black communities. If you were wearing Gucci, you weren’t necessarily helping black culture. You were just making rich people richer. I think it’s become more about community. About rising together as one through fashion or music. I think that’s why Skepta’s Air Max 97 SK did so well. Because there was this element of rising together. I think you’re starting to see people look after each other before anything else.’

In a way, it’s the same raw transmissions that powered pirate radio and pumped blood through silhouettes like the Air Max 95: a strong sense of community.

Get rich? Sure. But help the others tryin’.

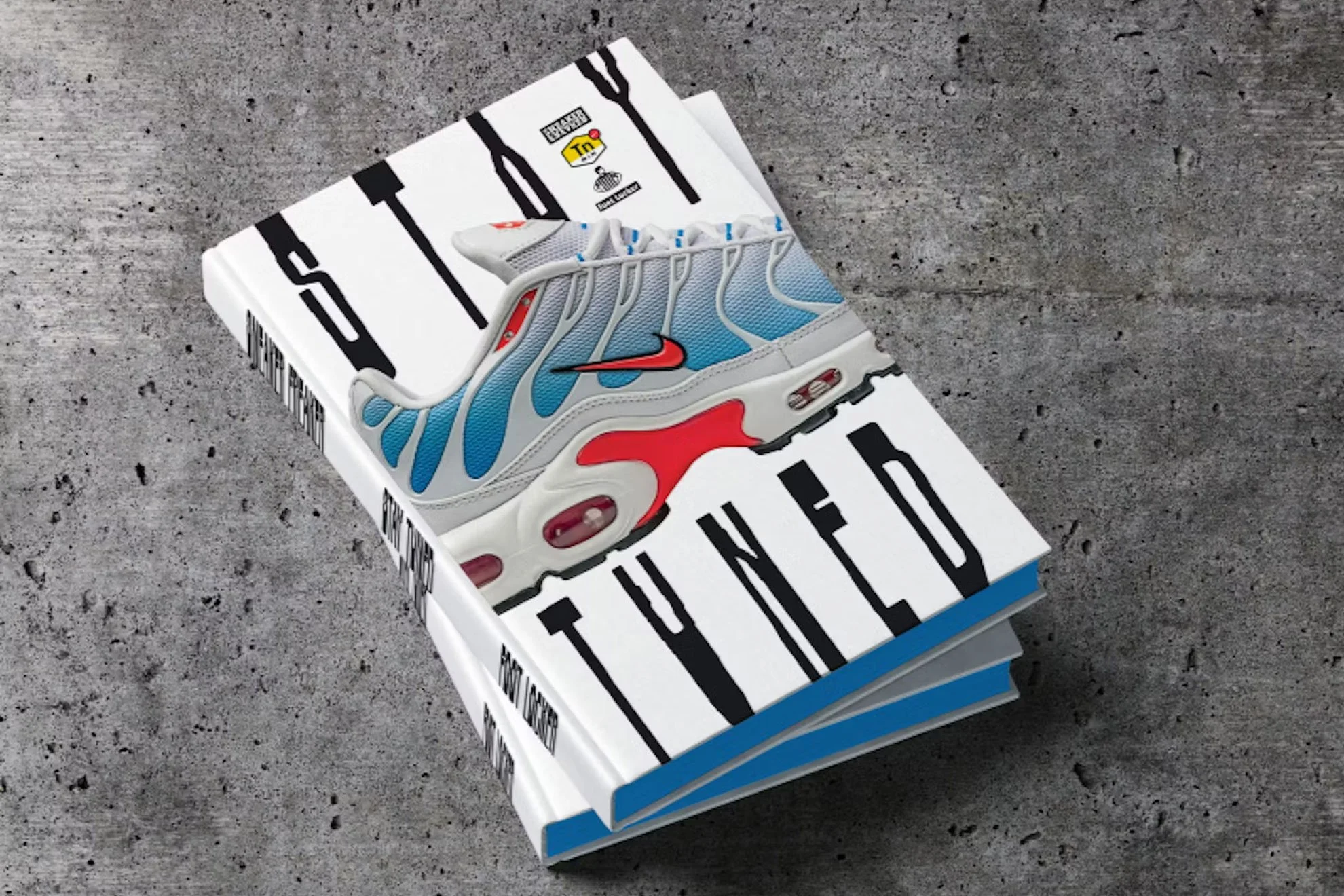

How the Air Max Plus Became the Kingpin Down Under

Foot Locker

The seven-bubble bad boy of Nike’s celebrated Air Max family, the Air Max Plus (AKA TN) is still the sneaker kingpin Down Under.

Stomping onto the sneaker scene in the late 1990s, designer Sean McDowell’s serene vision of Florida’s beaches was interpreted in Australia as a perfect spray-paint fade, or strange, alien-like ribs. Encasing the beating heart of burgeoning sub-cultures, the TN quickly leapt from its performance origins to arguably become the most notorious member of the Air Max dynasty, its popularity exploding most notably across enclaves in Western Sydney and Melbourne.

Leading the TN charge for over two decades, Foot Locker’s retina-burning Aussie-exclusives emblazoned the path for its extraordinary success, the beloved Air Max Plus quickly becoming a runaway success in the region.

With the rumoured release of Foot Locker's Air Max Plus ‘Lava’ retro bubbling on the horizon, we thought we’d revisit the inflammable legacy of the Nike TN Down Under: the wild child of Nike’s royal Air Max bloodline.

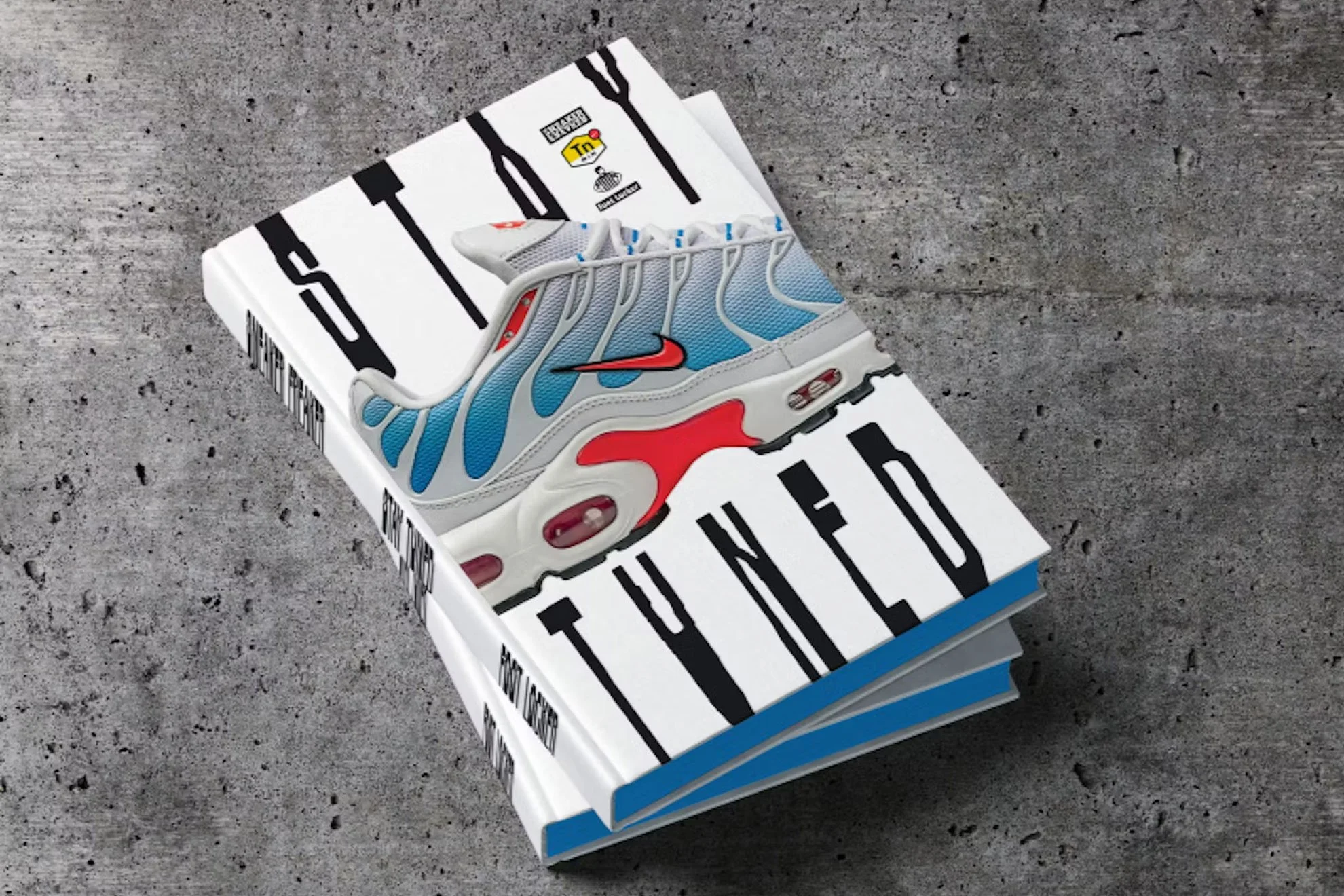

The Genealogy of a Transgressor: The Sky Air

The design ancestry of the baddest member of Nike’s Air Max family is, of course, anything but straight-forward. In 1997, Nike hired rookie designer Sean McDowell to work on the elusive ‘Sky Air’ project, a new running sneaker for Nike’s most important client: Foot Locker.

Little did McDowell know, his baptism was by fire.

Foot Locker had already rejected more than 15 proposals from Nike, the Manhattan footwear giant desperate to see Beaverton’s brand new cushioning system installed in an eye-catching silhouette. The technology was Tuned Air, a blow-moulded unit coupled with rubber hemispheres placed in the sole to provide support. A product of Nike’s moonshot design incubators in the 1990s, these ‘hemispheres’ allowed Nike to relieve the pressure on the heel, while also adding more cushioning to the forefoot.

The ‘Sky Air’ would utilise a trio of previously unseen manufacturing techniques, including McDowell’s lofty idea of a gradient fade – a central component to his ambitious vision.

‘As soon as I heard “sky”, I was like, oh my god, I just saw this amazing sky in Florida,’ McDowell recently told Nike. ‘I did a sunset. I did a blue one. I did a purple one. I tried a couple of different colours and sky versions, some palm trees were a little more tech-y and very geometric, and others were waving.’

For McDowell, the ‘Sky Air’ was almost a literal interpretation: you could lodge your foot right between the palm trees – as if you were walking on air. ‘It could make a quarter panel,’ McDowell remembers in his early sketches. ‘You could hold your foot down with those palm trees.’

The beachside doodles were a circuit-breaker for Nike. The Sky Air was finally signed off by Foot Locker, and would eventually become the Air Max Plus. But for the TN’s earliest adopters in Australia, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, this tranquil breeze blowing from Florida’s beaches was felt very differently.

The ‘Whale Tail’ That Breached Australia’s Underground

They say beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Well, so is the beast. In Australia, the TN’s postcard-perfect sunset was interpreted as a spray-paint fade (emblematic of Australia’s railway entrails in the late 1990s and early 2000s), while the swaying palm trees were perceived as ribs or swollen veins, ominously swelling across the mesh uppers.

‘I had no attraction to the TN when I first saw it in Sydney,’ says TN collector Raymond Ray. ‘I mean, it had spider-web looking veins running across the uppers.’ However, the pugnacious aesthetic appealed to Australia’s fringe and, when paired with the hefty $239.99 price tag (the highest ticketed item at Foot Locker at the time), the TN became a badge of honour for Australia’s defiant underground in the early 2000s.

‘It was the inherent “bad man” shoe’, says another devoted TN collector Jay M. ‘Searchers, lads. These were the types of characters originally wearing them. Honestly, they’d be taken from your feet if you crossed the wrong guy.’

Graffiti, rave, and eshay sub-cultures throughout Sydney’s Greater West and Melbourne all adopted the TN, Nike’s seven bubbles becoming part of a broader sartorial outfit usually featuring the likes of Polo, Nautica and, of course, the all-important bumbag.

For some early collectors, it was the TN’s connection to the badly-behaved Aussie underbelly that attracted them to the sneaker – not necessarily the design itself.

‘Members of that certain lifestyle loved to show off their “success” and keep fresh at the same time. Naturally, footwear is the go-to way,’ says Raymond. ‘The reputation from these sorts of characters that wore the shoe is what initially attracted me to the TN.’

Fuelled by Australia’s truculent outcasts and artists, McDowell’s ‘whale tail’ (the TN’s midfoot shank was originally modelled on a whale’s tail) soon breached the broader retail market at Foot Locker, and paved the way for over two decades of successful Aussie-exclusive colourways.

A Rogue Son Rises

Retina-blasting colourways have become fundamental to the TN’s enduring success in Australia. Originally ignited by the OG colourways – ‘Hyper Blue’, ‘Orange Tiger’, and ‘Grey Shark’– it didn’t take long for Foot Locker to start producing exclusive hits Down Under, including the ‘Tiffany’, ‘Fades’, ‘Sunburn’ and ‘Cactus’.

These bold Aussie-exclusives sparked the imagination of TN-heads. Around the same time, blogs and forums erupted in the digi-sphere, providing a place to debate, bemoan or blast all the latest releases. Those online spaces became a fiercely protected place for TN lovers. Debates routinely ignited over materials and shape, as well as manufacturing specifics around Made in Vietnam or Made in Indonesia models.

Foot Locker have been fundamental in shaping this dialogue and fuelling the TN's eye-watering success in Australia. 'You become an absolute sponge for what’s happening in sneaker culture,’ says one Foot Locker insider. ‘We’re monitoring tens, or hundreds of blogs constantly to see where the influences are coming from. The word that comes to mind is nurture. We want to do the TN justice. We want to stay authentic.’

One of the most passionate and incendiary sneaker fan bases in the world, there’s a lot of pressure surrounding every single Aussie-exclusive TN colourway.

‘The TN community is such an authentic, tight-knit community within Australia,’ says Foot Locker. ‘If we’re not in-tune (pardon the pun) with what’s in-line with customer sentiment on the blogs, then it makes it very difficult for our future aspirations.’

One of the more recent hits for the TN was undoubtedly the ‘Lava’ colourway. Originally arriving in 2015, the molten-hot TN hit shelves just months after Kanye West’s Nike Air Yeezy 2 ‘Red October’, and continues to be one of the more hallowed colourways in Nike’s vast Air Max Plus catalogue.

‘The Yeezy 2 Red October came out in 2014. It got me by nine months, so I’m wondering if that had a subliminal influence on me,’ our insider revealed. ‘But the objective with the “Lava” was to be really bold, premium and distinctive. I knew I had to disrupt the pattern of white mesh TNs.’

Outside of ‘Triple Black’ and ‘Triple White’ renditions, monotone colourways were scarcely seen during the TN’s fledgling years. Now, it’s one of the highest volume areas of the sneaker industry more broadly.

That shift has proven to be one of many evolutions we’ve seen from the TN over its 20-year history. From its early days as an OG Air Max agitator in ‘Orange Tiger’, to more recent iterations like the ‘Lava’, a whole new generation of sneakerheads are now eager to lace the seven-bubbled beast.

‘They’re more mainstream now,’ says Jay M. ‘They’ve become more accessible and trendy, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing. I think the shoe has finally gotten the recognition it deserves, and not shunned for its connotations.’

Gradually outgrowing its hard-edged heritage, the reputation of the Air Max Plus has certainly softened, and is now being embraced by a broader demographic in Australia. Still, that’s not to say that any of us forget how the Air Max Plus stomped its way to cultural prominence in the early 2000s. Whether we’re conscious of it or not, that indelible TN badge still pays homage to all the suburban backroads.

According to Raymond, ‘It’ll be a long time before we forget its history, or how the shoe built its notoriety’.

For Foot Locker, the Air of the future is still Tuned. The challenge lies in continuing to push the boundaries on a sneaker routinely shattering the status-quo.

‘What else can we do with it? What can we play around with?’ says our insider. ‘How can we press the boundaries? This is a silhouette that really allows us to do this.’

Yes, the TN continues to cast an interminable shadow across Australia’s sneaker culture. Whether these long silhouettes are palm trees blowing gently in the breeze, or protruding veins swelling from muscle tissue, we’ll let you be the judge.

The Converse One Star: Still Burning Bright in the Sneaker Cosmos

Client: Converse

The Converse One Star is still a guiding light for skaters and style savants across the globe. After a brief but bullish display on the NBA hardwood in the early 1970s, the One Star later found itself reimagined on the streets of Tokyo, the vintage model extolled as an emblem of American varsity fashion.

But it wasn’t until the 1990s that the One Star truly began to shine. And this time, it was at the skatepark. Roused from its slumber by the beloved rag Thrasher, the One Star kicked and pushed its way to become one of the industry’s breakaway success stories of the decade.

Now, reinvigorated by the CONS skate team and a growing roster of collaborators, the One Star is ready to carve up the competition all over again. So grab your board and basketball: it’s time to take a closer look at the emanating impact of one of the brightest stars in the sneakersphere.

Converse were consistently outmuscling their opponents during basketball’s nascent years. For decades, the Chuck Taylor was doing all the scoring on the hardwood, with NBA Hall of Famer Wilt Chamberlain loading the stat sheet.

In 1974, it was time to introduce the newest star to their roster.

‘The One Star was our next step beyond the Chuck Taylor’, says Sam Smallidge, Archive Manager at Converse. ‘It was the first time we’d used leather. Up until then, it was all canvas. The One Star had all the comfort and performance of the All Star, plus the evolution of the leather material.’

Originally dubbed the Suede Leather All Star, the sawn-off version was defined by its vulcanised rubber soles, new leather construction, and single star emblazoned on the lateral sides. Also boasting a lighter price tag, the model was laced by the likes of Julius ‘Dr J’ Erving, Bernard King, and several other professional players looking for a more streamlined silhouette. But after just two years, the model was benched in favour of the Pro Leather – a sneaker offering a newer, more responsive cup sole.

Despite sitting dormant in the United States for a number of years, the One Star nevertheless found a robust pulse in unexpected markets. In fashion meccas like Harajuku, Japanese acolytes of Americana desperately rifled through stores in search of the One Star and other sartorial remnants from the 1970s. Praised for its streamlined suede construction and connection to the Ivy League style, Japan kept the One Star’s glow strong despite the interest waning stateside.

But this was all about to change.

In 1993, it was time for the remodelled Converse One Star’s rip-roaring comeback. And this time, it was the skaters and street urchins that gave the model its eye-peeling momentum.

Broadcast to the world via Spike Jonze’s skate opus Mouse (where tech extraordinaire Guy Mariano famously laced the sneaker) and Thrasher magazine in the mid-90s, the One Star was getting huge air. With a burgeoning skate scene, an attractive price point and a better board feel, the One Star was blazing.

‘Thrasher was a national publication, so it pushed the One Star’s influence across the entire US’ – well beyond just the East Coast,’ says Smallidge. ‘And after several lifestyle iterations, you really see the One Star grow into its own little lifestyle brand within Converse’.

Further amplified by the ear-ringing influence of Seattle grunge and its disgruntled godfather Kurt Cobain, the One Star was now a counterculture anti-hero. By the late 90s, it was entering a new millennium with sole-destroying speed.

The Converse One Star is maintaining impressive momentum in the 21st century thanks to a steady run of collaborations and an ever-expanding roster of CONS team riders. Recruiting Supreme skate duo Sean Pablo and Sage Elsesser, the team was given some shiny new hardware with the debut of a skate-specific One Star in 2015. After experimenting with several different performance technologies, the Converse team landed on CONS traction rubber outsoles and moulded CX sockliners, adding unprecedented levels of comfort and impact absorption.

On the collaborative front, the One Star also wasn’t warming the bench. Stateside raconteurs like Tyler, the Creator and Stussy have repurposed the silhouette for a streetwear-savvy audience, while godfather of Ura-Harajuku fashion Hiroshi Fujiwara has reinforced the model’s strong connections to Japan.

Not strictly limited to the model’s profound success in US and Japanese markets, the One Star has also stamped its passport all over the world, collaborating with Dutch masters Patta, Hong Kong’s CLOT, Milan’s Slam Jam and many, many more.

As we quickly approach the One Star’s 50th anniversary, Matt Sleep, head of collaborations at Converse, is keen to continue to bring a diverse portfolio.

‘You’re going to see a very heavy roster, moving through skate, lifestyle, fashion and streetwear. We’re going to be touching on the historic elements that made the One Star so popular.’

With a radiant constellation of collaborations, skaters and devotees the world over, the One Star continues to emit a glow that reaches both new and established sneaker cultures around the globe.

Ready to go star-gazing? Shoot over to Converse to shop all the brightest sneakers in the galaxy.

How the Air Max 97 'Silver Bullet' Shot Through the Heart of Italy

Sneaker Freaker

Designed by a young Christian Tresser in 1997, the Nike Air Max 97 ‘Silver Bullet’ shot right through the heart of Italy in the late 1990s. Affectionately nicknamed ‘Le Silver’ by locals, the AM97 was shaped like industrial liquid, Tresser’s metallic, bicycle-inspired design firing-up the fever-dreams of Italian futurism. Pedalling relentlessly into the future, the AM97 was lovingly laced by Italians from all walks of life, from dealers to DJs, models to street artists – it was love at first sight.

This is the story of how the supersonic Air Max 97 found a place in the heart of Italy’s burgeoning sneaker scene.

![When Christian Tresser first started work on the Air Max 97, the pressure was mounting. ‘This shoe is going to make your career,’ he was advised, ‘Don’t blow it.’ ‘[The 97] had already been through two designers before me,’ Tresser remembers in Lod](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a0bbf488a02c79659049517/1653979354188-EATQ1WICE27AYQNLODW2/am7+2.jpg)

When Christian Tresser first started work on the Air Max 97, the pressure was mounting. ‘This shoe is going to make your career,’ he was advised, ‘Don’t blow it.’

‘[The 97] had already been through two designers before me,’ Tresser remembers in Lodovico Morano’s seminal book, Le Silver. ‘Being an avid competitive cyclist, I had my eye on the mountain bike world. I thought mountain bikes looked very futuristic ... I headed into the materials room and just plonked down the sample books and started cutting stuff out: metallic fabrics, 3M and, again, meshes. These combinations of materials felt really good to me, really right.’

For Tresser, the image of the bicycle was the perfect articulation of speed and futuristic aesthetics. Pairing the industrial dynamics of bicycles with the image of a water droplet radiating outwards from a puddle, Tresser conceived the Air Max 97. The very first sneaker to introduce a full-length Air unit, the silhouette was emblazoned by the industrial ‘Metallic Silver’ colourway, a high-speed, mechanised silver and titanium palette that had particular appeal for those in Milan – the manufacturing heartland of Italy.

In many ways, Tresser’s original blueprints were echoing the rattling, raucous voices of the Italian futurists of the early 20th century. In the minds of the futurists, the bicycle embodied ideas of machine-devotion, speed and youth. In the words of F.T. Marinetti in The Manifesto of Futurism from 1909, ‘We declare that the splendor of the world has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed.’

The Air Max 97 ‘Silver Bullet’ struck a chord in Milan. When it first released in 1997, the sneaker was glowing on the shelves like remnants of an alien spaceship.

‘They looked like they were from another planet,’ says Sha Ribeiro, a member of the graffiti group Lords of Vetra. ‘I mean, wearing them, you look like a fucking alien from another planet entirely.’

In the bowels of Milan, the Lords of Vetra bombed the city’s entrails, simultaneously lighting up the underground with the Air Max 97’s polyurethane midsoles and supersonic 3M reflective details. Named after the park Casa Vetra in the middle of Milan, the Lords of Vetra dedicated their youth to graffiti and everything that came along with it – tagging, bombing, drinking and stealing.

As a child, Ribeiro would fly with his father, a flight attendant, to New York City, where he would buy Nikes (still not readily available in Europe at the time). Ribeiro still remembers the first time he saw the Air Max 97. It was Christmas Day, 1997.

‘They cost around 150 euro, which was a shit-load of money at the time. My birthday was around Christmas time too, so I asked my mum if I could have them for birthday and Christmas. We went into the store and they didn’t have my size. I ended up wearing a size lower and my feet hurt like hell for an entire week. After that they stretched and it was fine.’

Riberiro’s experience didn’t exist in a vacuum. Italians in the 1990s were becoming more and more conscious of American and English brands – usually through family and friends travelling to style meccas like New York City and London.

Sabrina Ciofi, the fashion editor of Sport & Street Collezioni in the 90s, grew up in Florence. Like Riberiro, she was also exposed to the American and English zeitgeist through her father, who travelled for work.

‘He brought us incredible stories, photographs, music, but above all, clothes and sneakers by brands that did not exist yet in Italy,’ says Ciofi. ‘I started to get passionate about English and American clothing and sportswear brands. Their aesthetic expressions later became the basis of my professional choices. We made zines, exhibitions of graffiti artists, imported brands such as Stüssy, Carhartt and Supreme, and tried to explain what their origins were.’

Before the AM97, Italy’s matrix of subcultures largely adhered to their strict aesthetic parameters. Rich kids wore Stan Smiths. Scenesters at the club wore Buffalo. Graffiti kids wore PUMA or adidas. But when the AM97 arrived, it evaded any one, monolithic cultural definition.

‘Honestly, to me they seemed ugly and tacky, but they were the perfect sneaker to introduce to the Italian mainstream,’ says Ciofi. ‘The 97 allowed Nike to become ‘The Brand’ in Italy, and form the basis of the new wardrobe for anyone aged 0 to 100.’

The fact that the AM97 had no strong ties to any sport or subculture allowed the sneaker to become the ultimate chameleon, a sneaker with an enviable clean sheet, if you will – which is more than can be said of Italian parliament at the time.

In fact, the Air Max 97 arrived at a historic period of social and economic upheaval for Italy. The Mani Pulite (the so-called ‘Clean Hands’ operation) had uncovered rampant corruption in politics that shook the nation to its core, and Italy was struggling to heal from the economic and moral implications.

In a way, arriving like Riberia’s blazing AM97s in the underground, the sneaker lit-up Italy in a loud, unapologetically lurid glow that radiated collective pride. The return of the Italian la bella figura.

As is often the case, it was the burgeoning club culture that best captured the spirit of Italy in the late 1990s, and the Air Max 97 was playing a huge role in that sphere. Bringing together Italians from all walks of life, the AM97 became one of the sartorial hallmarks of this new era.

‘The 97 felt like proper gold fever,’ says Luca Benini, who founded Slam Jam in Ferrara in 1989. ‘Really. It was the first sneaker to allow people into the clubs at the time.’

Of course, Italy is now recognised as a forefront of sneaker culture and streetwear (thanks largely to bricks-and-mortar storefronts like Benini’s Slam Jam), but it wasn’t always the case.

‘Back in the days before the AM97, you weren’t dressed well if you wore sneakers,’ says Ciofi.

For a country literally shaped like a designer boot, the idea of wearing sneakers to a club was sacrilege. But in the following years, the Air Max 97 would infiltrate Milan’s high-fashion circles, paraded down the runway by legendary figures like Giorgio Armani, and lauded by Italian street culture.

For those in Italy, ‘Le Silver’ forged deep-rooted emotional connections that remain to this day.

According to Ciofi, ‘The AM97 was a unique and absolutely all-Italian phenomenon linked to a time when street life in Italy was particularly fervent. That has not yet been repeated.’

The ‘Silver Bullet’ pierced the affections of a nation uniquely sensitive to the amorous contours of the heart. And while you never forget your first love, if anyone is going to fall head-over-heels for a boisterous, bawdy brutto-bello again, it is of course, the Italians.

What it's Like to Be Lost at Sea

VICE

Josh Marsh was holiday in the Philippines in 2012 when a boat he was on capsized off the coast of Manila. For the next 52 hours, Josh, his friend Tom, and Tom's dad were stranded on board with no shade and no supplies. Their tour guide, Ruben, dove from the boat and tried to swim to shore for help. It was the middle of December, with temperatures hovering around 31 degrees. Ships passed without stopping. They thought they were going to die.

With a few years between himself and this very close call, Josh sat down to tell VICE what it's like to survive being lost at sea. We talk dehydration-induced hallucination, sharks, and why he decided to save a bottle of Tanduay rum.

VICE: Hey Josh, so just to set the scene: you were visiting the Philippines a couple of years ago with your friend, Tom, and his dad. Why did you decide to take the boat out that day?

Josh Marsh: We were staying in Banton, an island near Manila. The plan was to head to Marinduque, which is about a 40-kilometre crossing. We were warned of rough weather and waves, but our guide insisted it would be okay to get across. Once we took the boat out, the weather turned quickly, and the engine started taking on water. Eventually, it conked out and we started bucketing water. We drifted sideways and were picked up by a big wave, it capsized the boat pretty quickly. We were all floating in the ocean trying to figure out what happened. Then we started grabbing whatever we could find floating up from the boat. The first thing I grabbed was a bottle of rum...

Wait, the first thing you grabbed was a bottle of rum?

Yeah. It was decent rum, and it was the first thing I saw floating up.

Was it expensive?

About $6 a bottle.

![What else did you grab? Our guide, Ruben, grabbed a kitchen knife and dove underwater to cut the [boat's shade] canopy free so we wouldn't be dragged under. Then we climbed to the hull of the boat and sat there trying to figure out what to do. Rub](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a0bbf488a02c79659049517/1699202517790-I4UPUPAQ376S2VQMYON9/vice.jpg)

What else did you grab?

Our guide, Ruben, grabbed a kitchen knife and dove underwater to cut the [boat's shade] canopy free so we wouldn't be dragged under. Then we climbed to the hull of the boat and sat there trying to figure out what to do. Ruben decided to grab a diesel canister, tie it to his wrist [so he could float], and swim to shore to get help. The island was pretty far off by this point. We told him it wasn't a good idea, but he was adamant. He started swimming out to the island. We kept an eye on him for as long as we could until he disappeared behind the waves.

Did you think about swimming to the island too?

I thought about it. The other option didn't seem great—sitting on the boat, waiting to be rescued. The island was in the distance but it didn't look impossible to reach. It was one of those decisions you have to make. But I decided to stay on the boat with Tom and his dad.

So it was just the three of you on the boat?

Yeah.

At this point, what was going through your mind?

We were basically just waiting for Ruben to make contact with someone. The hope was that he'd reached the island and was sending help.

Do you know what happened to Ruben?

He was never found. He drowned at sea.

What was it like once the sun went down?

The first night was terrifying. There was no moonlight. We were cold and hungry and had no idea what was lying beneath the water. We could hear the waves coming, but we couldn't see them. That was probably the scariest thing: knowing that if a wave knocked you off the boat, you probably wouldn't have the strength to get back on. We were so physically drained… We knew once nightfall hit rescue wouldn't happen until the next morning, if at all. We had no light on the boat so we just sat there, in the dark. The waves were relentless and we were deliriously tired. That night bioluminescence lit up the water surrounding the boat. It was actually really beautiful. [There were these] tiny creatures in the ocean emitting this strange glow. We were all transfixed.

Were you okay, physically?

My leg was pretty sore from an accident I had earlier on the island—the leg had an open wound. So, in the water, I was pretty worried about sharks. But once the sun came up, our spirits were up in the hope of rescue.

Did any ships pass you in the morning?

Two ships passed us. We tried to flag them down to no avail. We were trying to signal them with a tiny camera flash, but we kept dropping into the gullies of the waves. It was a long shot. We were pretty defeated.

Once the sun came up, was it hot? I'd imagine the sun could be pretty full on out there without any shade.

I was very badly sunburnt, and it was impossible to keep hydrated as we didn't have much water. The heat stroke combined with sleep deprivation made it very difficult to get a grasp on reality.